Our kids are immersed in violent and despairing media every day, and it’s affecting what they write and share with each other. From the earliest days of telling tales around the campfire, violence in the stories we tell has played an important role. But not all violence is the same.

The morality of violence is important for students and caring adults in their lives to consider when they want to address violence in writing that they share with others. As I tell my students: Write whatever you need to write. But share only what is appropriate for the context.

Below are some questions that I ask my students to consider before they share work with violent content.

What is the intent of the violence?

Appropriate reasons to use violence

Some children writing violent stories have an honest need to explore the reasons behind human violence in an attempt to understand it. In that case, the violence in their writing will raise questions about where violence comes from and what we can do to address it.

Some children use violence to heighten the danger that their characters are in, to bring about a more satisfying conclusion when the protagonist is able to defeat the antagonist. As long as the violence is appropriate within the context, like in the Harry Potter series, this is also acceptable.

Some children use fiction to create parallels to real violence that they have read about and experienced. In this case, again, it is acceptable when they use their writing to try to understand the moral basis of human conflict.

Inappropriate reasons to use violence

Some children have not yet learned that violence in writing is not just a flavoring, like grinding pepper on their pasta. Their intent seems to be to shock and titillate their audience. The violence in their pieces is often couched in revenge fantasies. Usually the antagonist wins in these stories.

Even worse, in some of this writing the protagonist is the evil person doing the violence, and they suffer no repercussions for their acts. Sometimes there is a thin veneer of “the other guy had it coming” that is supposed to explain their characters’ evil deeds, but often the violence is simply there because the writer perceives it as fun or cool. In the words of a teen writer I work with:

“I think they are trying use their edginess to differentiate themselves from their more ‘square’ peers.”

In other words, they are trying to be “cool” kids. This is not an acceptable reason to share violent stories with other kids.

What is the context for the violence?

Appropriate contexts

Human stories of struggle often feature some amount of violence. In these stories, an individual or group is subjected to an unfair or discriminatory situation in which they are victimized by a more powerful group.

The Hunger Games is a good example. Katniss is not a violent person and tries very hard to maintain her moral judgment. But the government’s actions force her into a situation in which she has to make the decision whether to kill other people. Although quite violent, this series is deeply moral.

Inappropriate contexts

An immorally violent story sets the violence up as the main attraction. There is no particular justification for it within the context of the story. We are to accept that this is just an evil world, filled with evil people, and so it’s going to be fun to read about them.

Although I can’t come up with a mainstream published example because I choose not to read that sort of literature, Internet memes are rife with this sort of inappropriate violence. One student in my classes shared a piece based on a meme in which the narrator speaks about how fun it is to kill people. There is no context that explains his behavior, and no consequences for it.

Violence without context is always received by readers as a celebration of violence.

What is the nature of the violence?

Children’s stories have been full of violence since the beginning of time. The witch attempts to bake Hansel and Gretel alive! But in no mainstream telling of this book do we get graphic descriptions of the raised bubbles that form on their hands as they resist being put into the hot oven, and the smell of…

OK, I think you get the point.

Violence for children should be largely implied

A child who has been exposed to many violent images will visualize plenty of details that were left out of Hansel and Gretel. But a child who doesn’t have violent imagery in their head will take the violence at face value. The witch tried to bake them, but she failed. That’s all that the child needs to consider.

We do not need to put new violent images into children’s heads. The world is full of violent images that they already live with.

Violence for children should be countered with kindness

A story in which there is only violence is simply immoral and inappropriate to share with children. The story of humanity is the struggle against our worst impulses and toward our better ones. Every religion addresses this struggle and attempts to help believers with stories that show goodness as well as evil. Children’s literature, similarly, has always tried to impart a secular version of this moral view.

The same goes for what our children write to share with others. They need to balance violence in their writing so that they can train their own perspective away from anger and despair.

A Tale of Two Stories

Last year, students shared two stories in one week that couldn’t be more different. I will keep details of the stories private, but here is what they looked like:

Story #1: The “look at me I’m cool” revenge fantasy

In this story, a narrator whose situation is never defined hears voices telling them to kill others who wronged them. There is graphic description of a dead body. There is no reason to believe that the narrator is a decent person who is in a difficult situation. In fact, there’s no context at all. We just hear this narrator telling us about their anger and despair and expecting us to share in it.

End of story.

Story #2: The Jewish diaspora, with creatures

I have no idea whether my young writer knew that they were writing the story of Jews throughout history, but the parallels were striking. In the story, a person who belongs to a maligned race of creatures moves from village to village, attempting to find others like them and acceptance from general society.

There was some violence in the story, including one member of the group being put to death. But there was only one detail, no titillation, and clear understanding in the context of the story that this person’s killing was immoral and caused anguish to the others.

It was also clear to any reader that this story was an exploration of what happens when a minority group is misunderstood and maligned. This was written by a child, certainly, but a child who was grappling with what it means to be a decent person.

Violence can be moral

Children’s fiction without conflict is the Bob books. Dick and Jane. In other words, books that attempt to do nothing but teach reading skills. Real literature explores conflict, and conflict is uncomfortable.

Not all conflicts in children’s reading need to be violent. But there is a place for appropriate violence. I believe that reading Anne Frank’s diary and learning about World War II permanently shaped my view of moral behavior in societies.

I can hardly imagine this, but what if the book I had read was an unapologetic diary of a Nazi soldier who enjoyed killing people…written for children? Even if that soldier had been put to death in the end, the point of a book like that would have been to teach me to despair that humans can act in moral ways.

What can we do?

I’ll end where I started: I encourage my students to write everything in their heads. I encourage them to keep journals and explore their worst thoughts if it helps them.

But when we share our writing with others, we are making implicit moral choices and making explicit declarations of who we are as people. I encourage all parents to ask their kids these questions, and then listen to the answers.

Related:

Comments

4 responses to “On moral violence”

Great topic to discuss, Suki! I have a similar issue when choosing books and movies to share with my kids/teach. It is so hard to find worthwhile literature that is completely sanitized–Pollyanna, after all, went from being a treasured literary friend to a name used with scorn against willful naivety. Readers, even kids, want stories that they recognize are somehow true to the world, stories that matter. (I do think there is value in Pollyanna, and her story can matter–but no one believes kids can/should live in her world.)

One of my favorite juvenile fiction series is The Mistmantle Chronicles–Narnia-esque animals are the central figures, and the stories are extremely moral (all the stories revolve around “good” vs “evil” plot lines, with characters having to weigh difficult choices, fight to save lives, etc.) The stories are also almost shockingly violent. In the very first book, a baby prince is stolen and murdered. In another book there is infanticide being practiced. In another one there is a terrible war. The books are FULL of violence, so much so that I warn the same parents I recommend them to. But still, the books are so worth reading, for kids who can handle it, and for families who are ready for those discussions–because all the violence is based upon the sad truths of history and human reality. So the books become moral tales, which make me think of the things Gandalf says in The Lord of the Rings, about how we don’t get to choose the time we are put into, we can only choose what we do with the time we are given. The books ring as true, and I personally find a great deal of spiritual allegory for fighting the good fight in them.

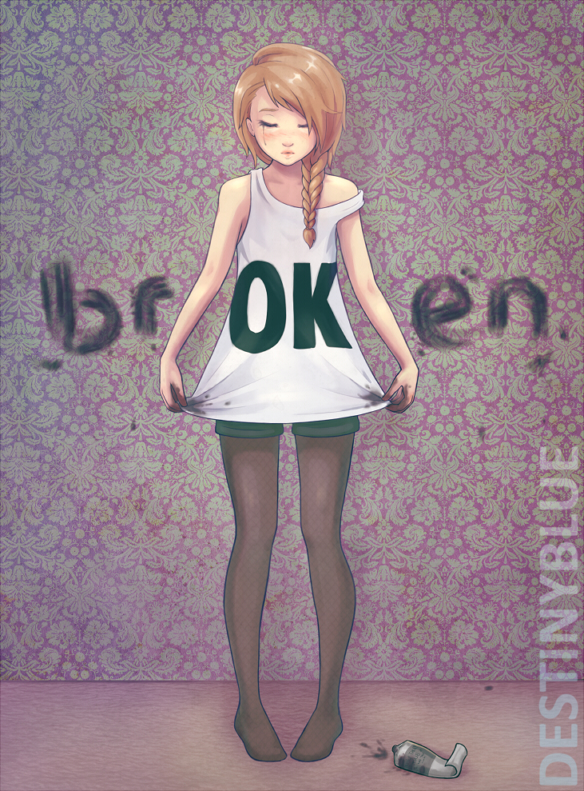

By the way, the art piece you chose, “Broken,” is quite moving. That’s a great work to discuss with teens too!

Thanks for your thoughts, Lisa. I haven’t read The Mistmantle Chronicles. They sound great – and thought-provoking. I agree that presenting kids with only whitewashed versions of reality (even when the “reality” is fantasy fiction) doesn’t serve them well. Even kids who don’t like to read violent literature tend to want the stories to matter, and when you make things matter, something has to be at stake. If there is nothing at stake, there’s no reason to read the story. So violence isn’t necessary, but since it’s a part of the human experience, kids need a way to process it and figure out what it means. Putting it into contexts where there are characters you care about suffering from and fighting against injustice is really the only moral way to present violence to kids. You reminded me of when I listened to the Inheritance Cycle with my kids on audiobook in the car. The first book, Eragon, is a lovely book completely appropriate for kids. There was a firm moral foundation to it. But as the series continued, we started referring to it as “Blood and Guts,” as in: “OK, we’re only driving for ten minutes—should we listen to Blood and Guts or wait till later?” It’s like the author got drunk on the ugliness. And the moral of the story ended up being something like “don’t bother to try to do the right thing because your destiny is unchangeable and it’s a waste of time to fight it.” I was really disappointed, though I have to say, it did engender lots of great discussion in the car!

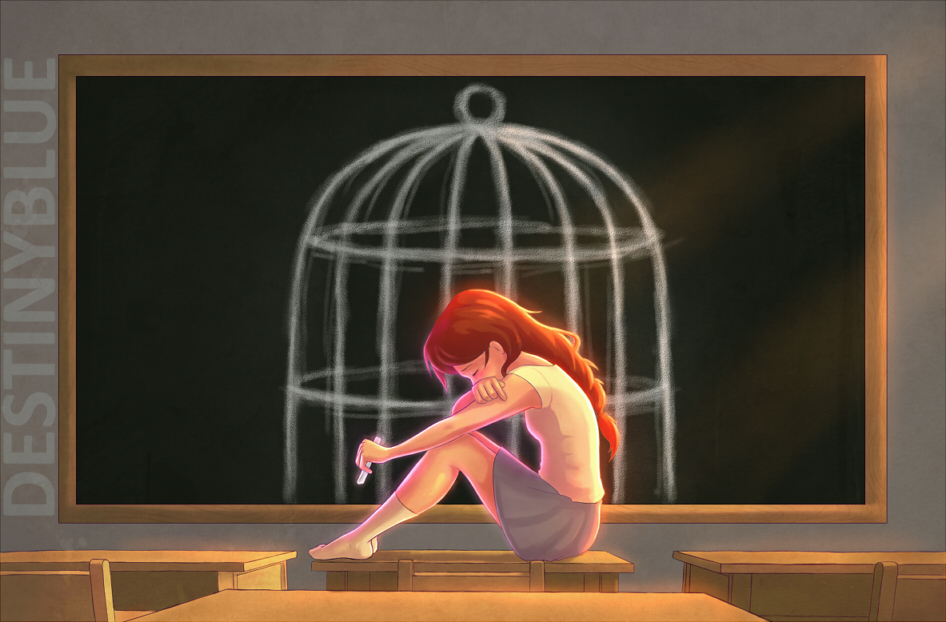

Thanks to teen artists on Deviantart for making their art available for use through Creative Commons! I love to feature teens’ work, and yes, I agree that it’s a thoughtful one.

That’s so interesting–as if this published author fell into the very trap you were writing about in this article, of writing about violence to be “cool” or to meet some perverted expectation of your audience. I love movies even more than books–so much that’s what my MH is in–but I have found I have no interest these days in staying current with Oscar-winners, the “cool” things to watch, etc. Too gratuitous, too indulgent in what offends for the sake of being edgy or trendy. I don’t feel like I’m missing out.

Yes, the author was quite young at the time (he started writing the series as a homeschooled teen, I believe) and I feel like it really degraded as it continued. The first book had such heart! It’s very hard in this world of always-connected activity to check out of things. I agree with you that we would all benefit by being less worried about following trends. Not all trends are worth following!