Category: Culture

-

Review: Getting gifted homeschoolers (almost) right

As a teacher of gifted learners, I am always interested in how they are portrayed in kids’ books. Generations of smart kids had to see themselves portrayed as clueless, clumsy, antisocial idiot savants. The Miscalculations of Lightning Girl avoids almost all the tired all tropes.

-

‘First world problems’ are everyone’s problems

When someone replies to your expression of despair with the phrase “first world problems,” they are dismissing you. They are saying that your despair is not valid, that by expressing your despair, you are insulting the millions who suffer greater physical distress than you do.

-

Fear of saying anything at all

As an interviewer, I have noticed what seems to be a growing trend. Perhaps it’s not a new trend, but it has been standing out more and more starkly in interviews. I’ll attempt to get my interviewee to something, anything quotable, yet they keep falling back into vagueness, empty jargon, and platitudes. I’ve been pondering…

-

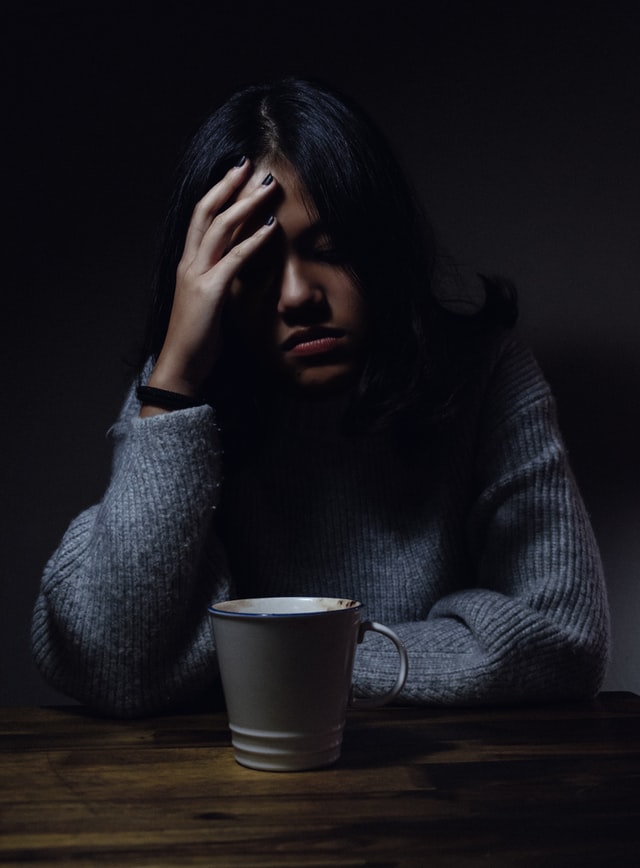

Resist irrationality: fight or flight in a time without lions

We humans obviously needed our fight or flight response in the past. When faced with a hungry lion, we needed to be able to bypass our pre-frontal cortex “professor brain” and act quickly. But although fight or flight is very useful in situations of physical danger, it’s become maladaptive for modern times.