Category: Education

-

What are your kids watching?

This one school year, I have had more students referencing violent memes, more students taking part in destructive and deceptive communities, more students writing about violent fantasies. Do you know what your child is watching?

-

Young writers’ reading list

The most important thing that young writers can do to develop their skills is write, write, and write some more. In conjunction with writing, young writers should read great writing: fiction, nonfiction, poetry, jokes, text messages…. The form doesn’t actually matter. The more great writing they read, the more the rhythm of language will take…

-

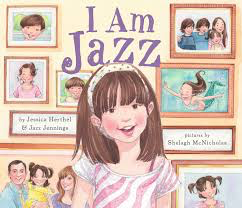

“I Am Jazz” Community Reading

This month Santa Cruz families will come together to read a book at the library. Yes, this happens all the time, but not with this book and this message. “I am Jazz” was published in 2014, co-written by 14-year-old Jazz Jennings, a transgender activist whose life had been profiled in a television documentary. Although the…

-

The value of creative writing: a spoonful of sugar

Recently, one of my online creative writing students expressed great pleasure at the end of class for having spent an hour “not learning anything.” I let it slide, happy that he couldn’t see me at my desk, laughing at the success of my pedagogic deception. My students are learning—they just don’t know it.

-

Gifted Kids: The disconnect between input and output

It’s hard to educate a child who is profoundly asynchronous, as many gifted children are. While a young gifted child may have a high school level vocabulary, they may struggle to hold a pencil. And the disconnect becomes even more pronounced as the child grows and seems to become more mature. When a child can…